National cybersecurity vs. malware

Ukatemi Technologies

05/09/2023

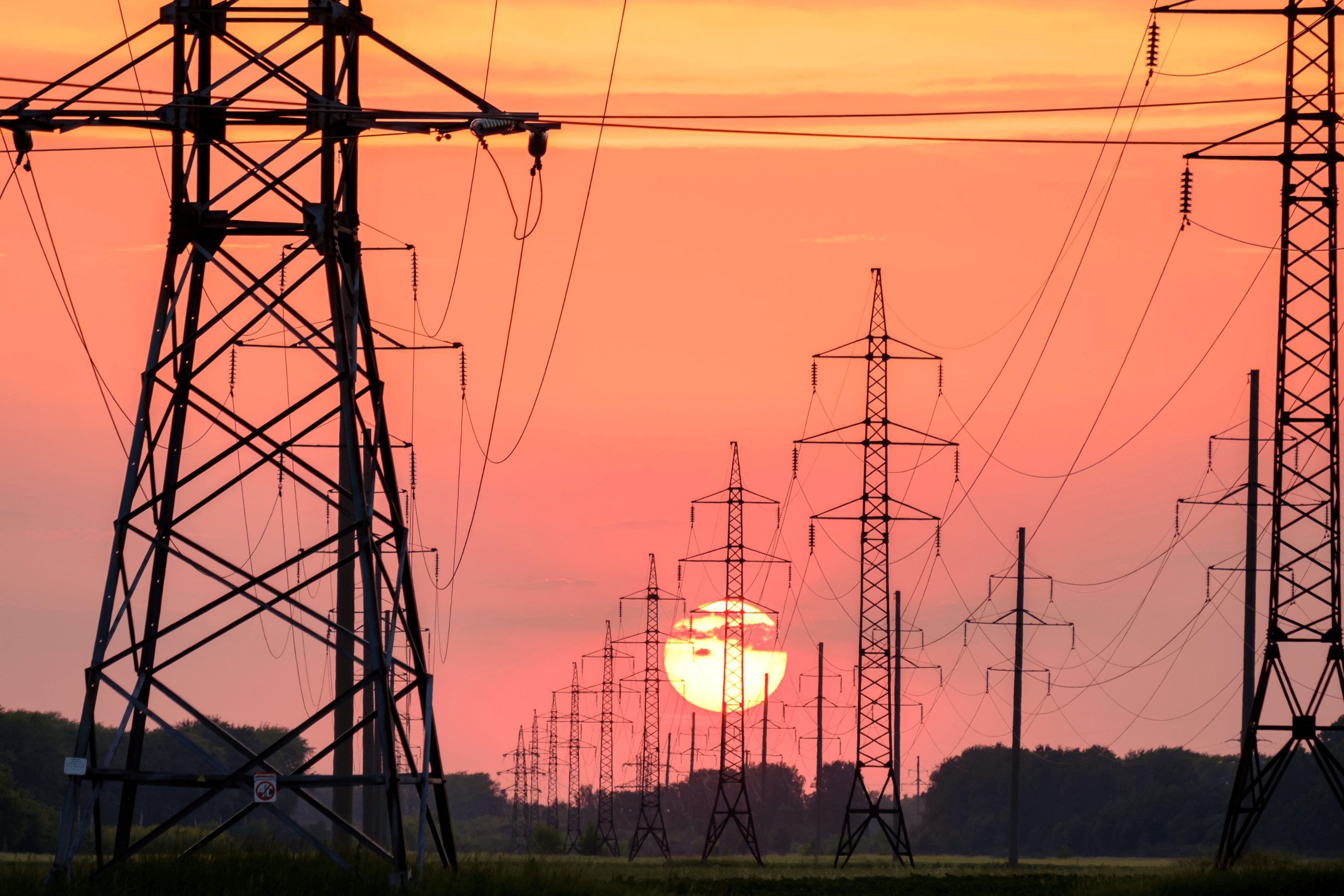

The beginnings – cyber attacks that wrecked states

As critical infrastructures become more digital, their cyber security vulnerability has increased. When these systems are compromised, it is certainly the general public that suffers the most, regardless of whether the state or the operator was responsible for the security of the particular infrastructure. In some ways, attacks on critical infrastructure can be seen as an attack on countries, which governments can defend against in a number of ways: through incentives or specific regulation to force operators to achieve a higher level of cyber security, or by developing their own capabilities (like malware analysis). To illustrate how real this threat is, here are some examples:

- In 2010, Stuxnet worm was discovered targeting Iran’s nuclear program. The worm was designed to specifically target the computer systems controlling centrifuges used in uranium enrichment causing physical damage to the equipment. (Although this system was not critical infrastructure in the classical sense, we are still talking about a serious cyber-physical system under state control.) The attack had significant geopolitical implications, underlined the existing concerns about the potential for future cyberattacks to cause physical damage or harm to individuals, and highlighted the need for increased cybersecurity measures to protect critical infrastructure.

- In 2017, the WannaCry ransomware attack affected over 300,000 computers in 150 countries, including several state organizations. The attack exploited a vulnerability in the Windows operating system and encrypted users’ files, demanding payment in exchange for a decryption key. The total damage caused by the attack is estimated to be around $4 billion.

- Also in 2017, the NotPetya malware attack targeted Ukrainian government systems and quickly spread to affect companies around the world. The attack is estimated to cause damages over $10 billion.

- In 2020, it was discovered that a sophisticated cyber espionage campaign had been carried out against the U.S. government and other organizations through the SolarWinds software. The attackers gained access to numerous systems and stole sensitive data. The full extent of the damage caused by the attack is still unknown, but it is estimated to have affected at least 18,000 organizations. The damages caused by the attack are also difficult to estimate, but it is expected to be in the billions of dollars.

These are the main public examples. We have no idea how many attacks have actually occurred. Some of them may not have come to light or may not have been publicized, this list is probably just the tip of the iceberg. Malware (and malicious cyber activity in general) is a real threat to peace all around the globe, it is not without reason that cyberspace is called the fifth domain of operation.

Defense lines, zigzags and dashes

Operators of critical infrastructures (both state and business organizations) constantly improve their defense mechanisms to protect against cyber attacks:

- strengthening their cybersecurity infrastructure (network security, access control, endpoint protection, software updates and patching, etc.)

- appropriate zoning of the infrastructure in compliance with standards (e.g., CISA)

- implementing multi-factor authentication when possible

- using antivirus and anti malware software

- conducting regular security audits

- user awareness trainings.

Despite these efforts, there are still gaps in the defense mechanisms of many states. One of the main challenges is the rapidly evolving and asymmetric nature of cyber threats, which can make it difficult for states to stay ahead of attackers. Additionally, many states may not have sufficient resources or expertise to fully protect against all possible cyber threats.

Another challenge is the growing sophistication of cyber attacks, including the use of advanced techniques in supply chain attacks. These attacks can be difficult to detect and prevent, even with the most robust defense mechanisms in place.

Overall, while states are taking steps to defend against cyber attacks, there is always more that can be done to improve their defenses and address any gaps that may exist. In our experience, states are mostly only prepared for the eventuality of repulsing an attack, but less prepared for what happens in the event of a successful attempt (e.g. they have daily/weekly reports on the malware attacks that might occur on their infrastructures, but they don’t have in-house analysis capabilities if an attack actually happens).

Low-probability things happen often

It is important to have reports on possible attack vectors, do regular updates, use 2FA etc. It is also important to know what to do if something happens despite these efforts. Our Kaibou product does exactly that:

- Kaibou Lab: a ready-to-use secure malware analysis platform (both hardware and software components), with fully tested tools and validated features

- Kaibou Repo: an extensive collection of malware from the last 20 years to minimize response time in case of an attack and to be able to practice in peacetime

- Training: it takes in-house experts from beginner to intermediate / from intermediate to advanced level in malware analysis or any other cybersecurity topic required.

See more about Kaibou product >>

Several things have happened in recent years that we never thought were possible. The pandemic. Brexit. The Russian-Ukrainian war. If only the next once-in-a-lifetime event didn’t catch us unprepared. Developing the cyber defense capabilities of states and supranational organizations is absolutely doable, especially before an incident, but remember that preparation must also address the scenarios that would apply in the case of a successful attack.

Here are a few links to keep you up at night:

https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/cybersecurity-advisories/aa22-110a

https://www.techtarget.com/searchsecurity/feature/Ransomware-trends-statistics-and-facts

https://securelist.com/it-threat-evolution-in-q3-2022-non-mobile-statistics/107963/

https://informationsecuritybuzz.com/ransomware-trends-q4-2022-key-findings-and-recommendations/